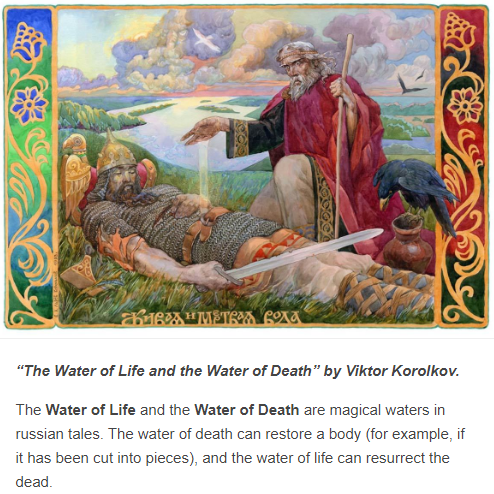

Surprisingly, folkloristics and ethnography can be helpful in further understanding how to come to terms with the past. The situation in which final death requires the complete restoration of the deceased and the hero must first be effectively killed in order to live on is not uncommon in Russian folk tales.

The image of the water of life and the water of death is too familiar to all of us from childhood to properly appreciate its oddity and mystery. Let’s remember how it works: the hero injured in a fight with a dragon is first sprinkled with the water of death. His wounds heal, the severed limbs grow back. He’s like new again, safe and sound, just dead. Now he has to be sprinkled with the water of life, only then will he come to life.

On the third day the raven came back again, bringing with him two little vials containing the water of life and the water of death, and gave them to the gray wolf.

The gray wolf took the bottles, tore the little raven in two and sprinkled him with the water of death, and the young raven immediately grew together.

Then he sprinkled it with the water of life and the little raven got up and flew away again.

Then the gray wolf sprinkled Ivan Tsarevich with the water of death and his body grew together again, and when he sprinkled him with the water of life, Ivan Tsarevich got up and said: – Ah, how have I slept so long?

At first glance, the logic seems clear: to revive someone, you must first heal the wounds. But why is it the water of death and not the water of life that has this effect? Why is a magic potion that heals wounds connected not with life but with death? Probably the best explanation for this riddle was provided by the philologist and folklorist Vladimir Propp in his book The Historical Roots of the Magic Fairy Tale:

The water of death gives the hero the deathblow, as it were, transforming him into a dead man for good. It is a kind of funeral rite, equivalent to throwing earth. Only now is he a real dead person and not a being suspended between two worlds who can return as a vampire. Only now, after being sprinkled with the water of death, will this water of life take effect.

The water of death shows – in the pointed form typical of myths – how drawing a line under the past works.

Anyone who advances into the future without closing the crime-ridden past belongs to two worlds. But to exist in two opposing worlds means not really belonging to either one, as the figure of the vampire teaches us.

To come alive, one must first die utterly. So that the past is no longer destructive for the future, it must come to light and be evaluated as a whole. Only then is it really complete.

Reconciliation

What a really productive coming to terms with the trauma of the past can look like, in which it is sprinkled with both waters, as it were, is shown by an event that is very important for our topic in many respects: the reconciliation between Denis Karagodin, who was investigating the execution of his great-grandfather , and the granddaughter of a man involved in this execution. Julija X wrote to Karagodin after reading about his research:

I haven’t slept for days, I just can’t … I’ve studied all the materials, all the documents that you have on your site, I’ve thought about so many things, remembered in retrospect … Rationally, I understand that I I’m not to blame for what happened, but I can’t put into words what I feel…

My grandmother’s father (on my mother’s side), my great-grandfather, was taken away from home in the same years as your great-grandfather after a denunciation and never returned. He left four daughters, my grandmother was the youngest… And now it turns out that there are both victims and perpetrators in our family… It hurts a lot to realize that… But I’ll never try avoid my family history, whatever it is. Knowing that neither I nor any of the relatives I know, remember, and love had anything to do with the atrocities of those years will help me endure it all…

The suffering caused by such people is irreparable… The task of the following generations is quite simply not to remain silent, all things and events must be called by their name. And my letter is just to tell you that I now know this shameful side of my family history and I am wholeheartedly on your side.

But nothing will ever change in our society until the whole truth comes out. It’s no coincidence that Stalinists and Stalin monuments have appeared again, it just doesn’t want to get into your head, it doesn’t make any sense.

I would like to write and tell you a lot more, but I have said the most important thing – I am very ashamed of everything, it causes me physical pain. And it is bitter that I can do nothing about it, except to confess to you my kinship with Nikolai Zyryanov and to commemorate your great-grandfather in the church.

Thank you for the tremendous work you have done, for the truth, however difficult it may be. It gives hope that society will finally be sober thanks to people like you. Thank you again, and sorry!

Here is Denis Karagodin’s answer:

Julia,

You wrote me a very sincere and heartfelt letter. This is an extremely bold step. I am sincerely grateful to you. I see you are a great person! That makes me happy and fills me with pride that I can write this to you straight out without bending my soul. You will not find in me an enemy or a tormentor, just a person who wants to annul this whole endless Russian carnage once and for all. It has to end for all time. And I think it’s within my power and yours to make that happen.

I extend my hand to you for reconciliation, as difficult as it is for me (with the current knowledge and memories). I suggest you reset the whole thing to zero. You did the most important thing with your letter – you were sincere, and that’s more than enough for everything.

Live with peace of mind and above all with a clear conscience. Neither I nor my family or friends will ever blame you for anything. You are a great person, you should know that. Thank you from the bottom of my heart…

Also in this exchange, which is partly reminiscent of a psychological group session, the category of “zeroing” appears.

But neither side tries to portray the crime as non-existent. On the contrary, both agree that »all things and events must be named«.

Both interlocutors are aware of two things.

Firstly, only remembering the crime and knowing how and why it happened and who was to blame ensures that it cannot happen again.

Second, civil society solidarity can only be built by striving to reveal the truth, to place and overcome what happened, and by striving to ask for and give forgiveness. “Setting to zero” here means forgetting what separates this past, draining the cadaveric poison out of it, removing the sting from it.

One way to do this is to draw a line to break the chain of mutual insults and revenge.

Excerpt from the book Uncomfortable Past by Nikolai Eplee

Not available in English, my translation from German publication